Overview

- Kenyanthropus platyops is a 3.5-million-year-old hominin from Lomekwi, Kenya, distinguished by an unusually flat face and small molars that set it apart from the contemporaneous Australopithecus afarensis.

- Its discovery in 1999 challenged the long-held view that A. afarensis was the sole hominin species in the middle Pliocene, revealing that multiple lineages coexisted in eastern Africa.

- The validity of the genus remains debated: some researchers argue the holotype cranium is too distorted to diagnose reliably, while others have used geometric morphometrics to confirm its distinctiveness.

For much of the late twentieth century, A. afarensis was regarded as the only hominin in eastern Africa between ~3.0 and 3.7 million years ago. That changed in 2001, when Meave Leakey and colleagues announced Kenyanthropus platyops based on a near-complete but heavily distorted cranium from western Lake Turkana, Kenya.1 The name means "flat-faced human from Kenya," reflecting its most striking trait: a remarkably vertical midface unlike the projecting snouts of most australopithecines.1 Although the taxonomic status remains contested, the discovery opened sustained debate about middle Pliocene diversity and the branching nature of human evolution.2, 3

Discovery and context

The Lomekwi site lies on the western shore of Lake Turkana within the Nachukui Formation, a well-dated Pliocene sequence. Between 1982 and 2009, excavations produced a substantial hominin collection dated to 3.5–3.2 Ma: two partial maxillae, three partial mandibles, a temporal bone, forty-four isolated teeth, and the holotype cranium.4, 5

In August 1999, research assistant Justus Erus spotted bone fragments eroding from sediments. They proved to be a largely complete cranium (KNM-WT 40000), bracketed by dated tuffs at ~3.5 Ma.1 A year earlier, a partial maxilla (KNM-WT 38350) had been recovered from higher deposits dated to ~3.3 Ma and was designated the paratype.1, 5

Leakey and colleagues published their description in Nature in March 2001, erecting the new genus Kenyanthropus. They argued that the combination of derived facial features with primitive neurocranial morphology distinguished the Lomekwi specimens from all known australopithecines.1, 2

Anatomy and the flat face

The defining feature is the flat, orthognathic midface. Where most australopithecines have projecting, snout-like faces, KNM-WT 40000 has a vertically oriented subnasal region more reminiscent of later Homo.1 Anteriorly positioned cheekbones and a tall, narrow nasal aperture reinforce the flat-faced appearance.1, 5

The molars are remarkably small for a hominin of this age, approaching the minimum recorded for A. anamensis, A. afarensis, and H. habilis.1, 5 This combination of flat face and small teeth contrasts sharply with the large-toothed, prognathic Paranthropus that would appear later.6

The neurocranium, though distorted, indicates a small brain (~350–450 cc), consistent with other middle Pliocene hominins.1, 7 This derived face combined with a primitive braincase is what led Leakey and colleagues to propose a distinct lineage rather than a variant of A. afarensis.1

Comparison of key cranial features across middle Pliocene hominins1, 8, 5

| Feature | A. afarensis | K. platyops | A. africanus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subnasal prognathism | Marked | Minimal (flat) | Moderate |

| Zygomatic position | Posterior | Anterior | Intermediate |

| Molar size | Moderate to large | Small | Moderate to large |

| Cranial capacity | ~400–550 cc | ~350–450 cc | ~420–510 cc |

| Nasal aperture | Broad | Tall, narrow | Moderate |

The distortion debate

Tim White immediately raised concerns about the holotype's reliability. In a 2003 Science commentary, he argued that KNM-WT 40000 had suffered severe expanding matrix distortion (EMD)—minerals crystallizing within the bone caused it to expand, crack, and warp unpredictably, breaking it into over 1,100 fragments before reassembly.2

White contended that EMD does not distort all dimensions equally, so the flat face could be an artefact rather than genuine anatomy. He recommended sinking Kenyanthropus back into Australopithecus.2

Supporters countered that the paratype maxilla KNM-WT 38350, not subject to the same distortion, shares the diagnostic flat morphology and small molars.1, 5 A 2010 morphometric reanalysis by Spoor and colleagues concluded that the Lomekwi maxillary morphology falls outside the A. afarensis range, supporting at least two species in the middle Pliocene.5

The debate remains unresolved. Some accept Kenyanthropus as valid; others prefer Australopithecus platyops; a minority question whether the diagnostic features are real at all.3, 9 What is not disputed is that the Lomekwi fossils demonstrate morphological diversity that a single-species model cannot easily accommodate.5, 10

Middle Pliocene diversity

K. platyops was the first major challenge to the view that A. afarensis was the sole middle Pliocene hominin in eastern Africa. The only earlier candidate was A. bahrelghazali, described from a fragmentary mandible in Chad (1995), which many regarded as a variant of A. afarensis.11

The case for diversity strengthened in 2015 with the description of A. deyiremeda from 3.3–3.5 Ma deposits at Woranso-Mille, Ethiopia, distinguished from A. afarensis by its robust mandible, smaller teeth, and anteriorly positioned zygomatic arch—features also inviting comparison with K. platyops.10 Together, these species suggest at least three or four hominins coexisted across Africa during this interval, undermining the linear, single-species model.10, 12

This diversity echoes later periods. By 2.0 Ma, at least three genera (Australopithecus, Paranthropus, Homo) coexisted in eastern and southern Africa.6 The Lomekwi evidence extends this taxonomic richness much further back, to periods previously thought dominated by a single lineage.1, 5

Temporal ranges of middle Pliocene hominin species (millions of years ago)1, 8, 10, 11

The Lomekwian stone tools

In 2015, Harmand and colleagues announced stone tools at nearby Lomekwi 3, dated to 3.3 Ma—the oldest known stone artefacts, predating the Oldowan by ~700,000 years.13 Dubbed "Lomekwian," these cores, flakes, and anvils show deliberate knapping, though less controlled than later Oldowan production.13

The proximity to K. platyops fossils has led some to suggest this species made the tools, as it is the only hominin currently known from the immediate vicinity at 3.3 Ma.13, 14 But the attribution is circumstantial: no tools were found in direct association with K. platyops remains, and A. afarensis was also present in the broader region.8, 13

Regardless of the maker, the Lomekwian artefacts demonstrate that stone tool manufacture began well before Homo appeared (~2.8 Ma), showing that intentional stone modification was not unique to our genus.13, 15

Connection to Homo rudolfensis

One of the most intriguing aspects of K. platyops is its resemblance to KNM-ER 1470, the famous flat-faced skull attributed to Homo rudolfensis (~1.9 Ma). Both share a flat midface, anteriorly positioned cheekbone roots, and a vertically oriented cheek region—uncommon among other australopithecines and early Homo.1, 16

Leakey and colleagues noted these similarities in 2001 and suggested K. platyops might be ancestral to the KNM-ER 1470 lineage.1 A 2003 cladistic analysis by Cameron recovered the two as sister taxa, implying the flat-faced morphology persisted as a coherent lineage for over 1.5 million years.17

Some have proposed transferring H. rudolfensis to Kenyanthropus; others have argued the reverse. Neither proposal has achieved consensus, but the parallels underscore the complexity of Pliocene-Pleistocene hominin phylogeny.3, 9, 16

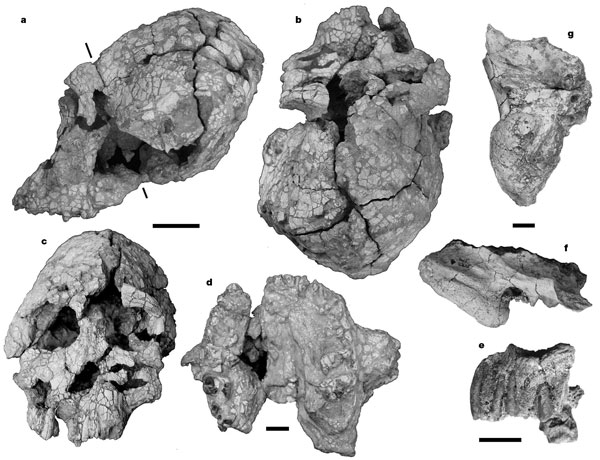

Key specimens

The sample is modest compared to A. afarensis. The holotype (KNM-WT 40000) is a near-complete cranium preserving much of the face, palate, and neurocranium. Despite severe distortion that broke it into over 1,100 fragments, reconstruction revealed the diagnostic flat midface, small dental arcade, and anterior cheekbones.1, 2

The paratype (KNM-WT 38350), a partial maxilla with less distortion, has been crucial to the debate: its flat subnasal morphology and small molars provide independent confirmation that the flat face is not purely an artefact.1, 5

Additional material—isolated teeth, mandibular fragments, and a temporal bone—comes from the same 3.5–3.2 Ma interval. While not all can be confidently assigned to K. platyops, their morphological pattern is consistent with a population distinct from contemporaneous A. afarensis.4, 5

Key specimens attributed to Kenyanthropus platyops1, 4, 5

| Specimen | Element | Age (Ma) | Year found | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNM-WT 40000 | Near-complete cranium | ~3.5 | 1999 | Holotype; flat face, small teeth |

| KNM-WT 38350 | Partial left maxilla | ~3.3 | 1998 | Paratype; confirms flat subnasal morphology |

Evolutionary significance

K. platyops matters precisely because its taxonomic status remains unsettled. Whether classified as a separate genus, an Australopithecus, or an aberrant individual, the Lomekwi cranium documents a morphological signal that does not fit neatly into A. afarensis.1, 5

The broader implication is that hominin evolution was branching and bushy. By 3.5 Ma, multiple species with different facial structures, dental adaptations, and ecological strategies occupied East Africa.10, 12 Determining which branches led where is the challenge, and K. platyops, with its resemblance to Homo rudolfensis, remains a key piece of the puzzle.1, 17

The association with the world's oldest stone tools adds a further dimension. If K. platyops or a close relative produced the Lomekwian artefacts, technological innovation was not confined to the lineage leading to modern humans.13 Combined with growing evidence for dietary and locomotor diversity among contemporaneous species, the middle Pliocene emerges as a period of adaptive experimentation from which our genus eventually arose.10, 18

References

Hominin diversity in the Middle Pliocene of eastern Africa: the maxilla of KNM-WT 40000

Middle Pliocene hominin diversity: Australopithecus deyiremeda and Kenyanthropus platyops

West Turkana Archaeological Project: 3.3 Ma stone tools and the origin of stone technology

New fossils from Koobi Fora in northern Kenya confirm taxonomic diversity in early Homo