Overview

- The genus Ardipithecus includes two species, Ar. kadabba (5.8-5.2 Ma) and Ar. ramidus (4.4 Ma), both discovered in the Middle Awash region of Ethiopia, representing some of the earliest known hominins.

- The partial skeleton of Ar. ramidus nicknamed "Ardi" preserves a mosaic of primitive and derived features, including an opposable big toe for tree climbing alongside a pelvis restructured for bipedal walking, showing that upright locomotion evolved before the loss of arboreal adaptations.

- Ardi's woodland habitat overturned the longstanding savanna hypothesis, which proposed that bipedalism evolved as a response to open grassland environments, and 15 years of painstaking preparation were required before the findings could be published in 2009.

The genus Ardipithecus—"ground floor ape" in Afar combined with Greek—comprises two species that document a critical interval in hominin evolution between approximately 5.8 and 4.4 million years ago.1, 2 Both were recovered from the Middle Awash study area of Ethiopia's Afar Rift, whose sedimentary deposits preserve an extraordinarily rich record of early hominin life. Together, Ardipithecus kadabba and Ardipithecus ramidus provide evidence for a grade of evolution that predates the australopithecines and offers a window into the earliest divergence of the human lineage from other African apes.1, 3

The significance of Ardipithecus extends well beyond its age. The 2009 publication of the partial skeleton "Ardi" (ARA-VP-6/500) challenged deep assumptions about how, where, and why bipedalism evolved. Ardi combined upright walking with powerful grasping feet adapted for life in trees, and she lived not on an open savanna but in a wooded environment.3, 4 These findings forced a fundamental reassessment of models that had dominated paleoanthropology for decades.

Discovery and naming

The first Ardipithecus fossils were recovered in 1992–1993 by Tim White, Gen Suwa, and Berhane Asfaw from sediments near the village of Aramis in Ethiopia's Middle Awash. The initial finds—teeth, jaw fragments, and postcranial elements—were published in 1994 as Australopithecus ramidus ("ramid" means "root" in Afar, reflecting the team's view that this species lay near the root of the hominin family tree).5 The following year, White and colleagues erected the new genus Ardipithecus, recognizing that its anatomy was too primitive to classify alongside the australopithecines.6

Fossils from older Middle Awash deposits were described in 2001 by Yohannes Haile-Selassie. Recovered between 1997 and 2000 from five localities, they dated to 5.8–5.2 million years ago. Haile-Selassie initially classified them as a subspecies, Ardipithecus ramidus kadabba.1 In 2004, after additional dental material revealed a more primitive canine morphology retaining features of a honing canine-premolar complex, the team elevated kadabba to full species status.7

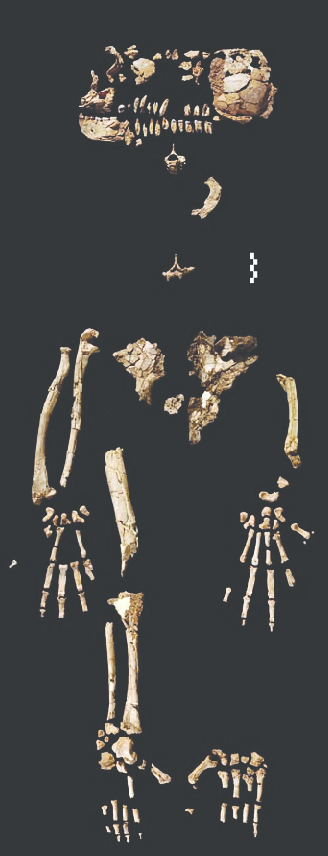

The most spectacular discovery, however, was the partial skeleton ARA-VP-6/500, spotted eroding from the surface at Aramis in November 1994 by Haile-Selassie. This individual, nicknamed "Ardi," preserved approximately 45 percent of the skeleton, including much of the skull, hands, feet, pelvis, and limb bones. The fossils were extremely fragile and crushed, and it took 47 scientists 15 years to excavate, digitally reconstruct, and analyze the remains.3 The results appeared on 2 October 2009 as 11 papers in a special issue of Science, which named Ardipithecus ramidus its "Breakthrough of the Year."3, 8

Ardipithecus kadabba

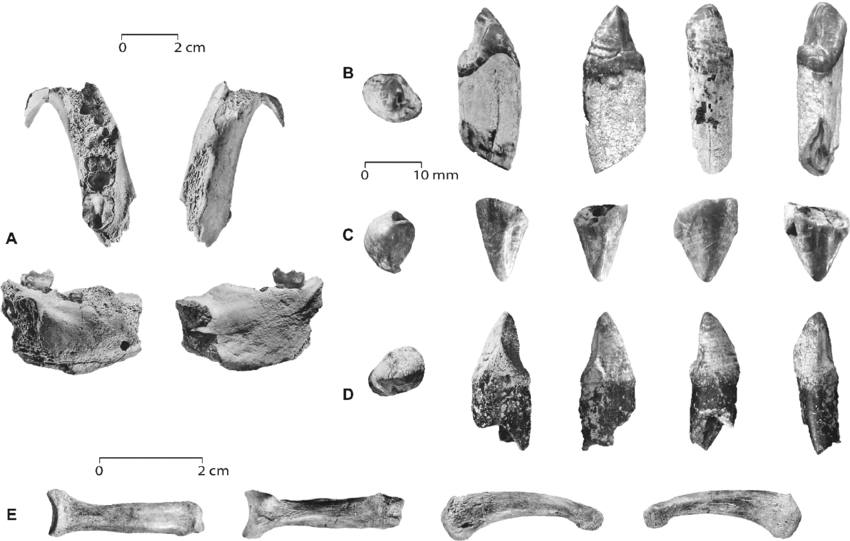

Ardipithecus kadabba ("basal family ancestor" in Afar) is known from nineteen specimens representing at least five individuals: teeth, jaw fragments, a hand phalanx, a foot phalanx, arm bone fragments, and a clavicle.1, 9 These come from localities spanning 5.8 to 5.2 million years ago, as determined by argon-argon dating of bracketing volcanic tuffs.1

The dentition is particularly informative. The canines are larger and more apelike than those of Ar. ramidus, retaining a functionally honing canine-premolar complex in which the upper canine is sharpened against the lower premolar during chewing. This feature characterizes living great apes and most Miocene hominoids but is reduced or absent in later hominins.7 Its presence in Ar. kadabba, combined with incipient reduction compared to extant apes, shows that canine reduction—a hallmark of the hominin lineage—was already underway by the late Miocene.7, 10

Evidence for locomotion comes primarily from a single proximal foot phalanx, AME-VP-1/71. This toe bone has a dorsally canted proximal articular surface, a feature associated with effective toe-off during bipedal walking, distinguishing it from the grasping configuration of extant apes and suggesting at least facultative bipedalism.1, 11 Some uncertainty remains, however: the toe bone was found roughly 15 kilometers from the other Ar. kadabba specimens and is somewhat younger, raising questions about whether it truly belongs to the same species.11, 12

The anatomy of Ardi

ARA-VP-6/500 represents a female who stood approximately 120 centimeters tall and weighed about 50 kilograms.3 The skull, badly crushed and requiring extensive digital reconstruction, reveals a small brain of 300 to 350 cubic centimeters—comparable to a modern chimpanzee and far smaller than the 400–550 cc of later australopithecines.13 The face is less prognathic than a chimpanzee's, and the skull base shows features consistent with a more centrally positioned foramen magnum, suggesting habitual upright posture.13, 3

The skeleton's most striking feature is its mosaic of primitive and derived traits. The pelvis departs dramatically from the ape condition: the iliac blades are shortened, broadened, and laterally flared, repositioning the gluteal muscles for side-to-side balance during bipedal walking.4 The upper pelvis thus resembles the hominin pattern, but the lower pelvis retains more primitive features, suggesting a form of bipedality more primitive than in Australopithecus.4

The hand provides equally important evidence. The wrist and hand bones lack any features associated with knuckle-walking in modern African apes. The metacarpals are short and the capitate bone is oriented to permit extreme wrist extension during palmigrade (palm-down) climbing on branches.14 The implication is profound: the last common ancestor of humans and African apes was probably not a knuckle-walker, and knuckle-walking evolved independently in chimpanzees and gorillas after the human lineage diverged.14, 15

The teeth show further canine reduction compared with Ar. kadabba. Male canines are only slightly larger than female canines, contrasting sharply with the large, projecting canines of male chimpanzees and gorillas. Enamel is thinner than in later australopithecines but thicker than in chimpanzees, consistent with a generalized diet of fruits, nuts, and other woodland foods.3, 16

The foot and the paradox of locomotion

No element of Ardi's skeleton generated more discussion than the foot. Unlike all previously known hominins, Ar. ramidus possessed a widely divergent, opposable big toe (hallux) that would have allowed powerful branch-grasping during arboreal locomotion.8 This directly contradicts the expectation that bipedalism and arboreal grasping were mutually exclusive. In Ar. ramidus, they coexisted in one individual.8, 4

Lovejoy and colleagues described the foot as reflecting both "prehension and propulsion."8 The big toe was opposable and grasping, but the lateral toes and midfoot show stiffening features that would have provided a rigid lever for pushing off during terrestrial walking. The overall structure suggests an animal that could walk bipedally on the ground—though less efficiently than later hominins—while retaining substantial climbing ability.8

This mosaic foot demonstrates that the pelvis was reorganized for upright walking before the foot lost its grasping capabilities, overturning models that assumed these changes occurred in lockstep.4, 8 The transition to obligate terrestrial bipedalism was a prolonged, piecemeal process rather than a single coordinated shift.

Woodland habitat and the savanna hypothesis

For much of the twentieth century, the dominant explanation for bipedalism was the savanna hypothesis: as African forests retreated and grasslands expanded, early hominins were driven to walk upright on the open plains. This model, rooted in Raymond Dart's 1925 interpretation of Australopithecus africanus, predicted that the earliest bipeds would be found in grassland environments.17

Ardi's paleoenvironment challenged that prediction. WoldeGabriel and colleagues (2009) published a detailed analysis of the geological, isotopic, botanical, and faunal evidence from the 4.4-million-year-old sediments at Aramis and concluded that the hominins occupied a wooded biotope ranging from woodland to forest patches.18 The associated fauna—colobine monkeys, kudu, peacocks, and small mammals—pointed to woodland, not the grazing ungulates of open grasslands.18, 3

The interpretation was contested. Cerling and colleagues (2010) argued that isotopic and phytolith data from Aramis indicated grasses constituted 40–65 percent of biomass, more consistent with a tree-savanna or bushland mosaic than dense woodland.19 White and colleagues responded that the critics had mischaracterized the data and that the faunal assemblage overwhelmingly supported a closed, wooded habitat.20 A 2011 follow-up proposed a "river-margin" model, suggesting Ar. ramidus lived near watercourses within a broader landscape that included both wooded and more open areas.21

Regardless of the precise canopy closure at Aramis, the evidence clearly shows that Ar. ramidus did not inhabit an open grassland. Even the most conservative reconstructions place the species in a mosaic habitat with substantial woody vegetation, fatally undermining the simple savanna hypothesis in which bipedalism evolved as a response to treeless plains.3, 18, 19

Fifteen years in the laboratory

The story of Ardi's publication is itself remarkable. When recovered in 1994, the bones were so soft and fragile they crumbled on contact, requiring field workers to extract them with their surrounding sediment matrix.3 White compared the fossils' condition to "wet calciumite"—each bone had to be consolidated in the field with preservative before extraction.22

In the laboratory, the crushed and distorted bones required years of micro-CT scanning and digital reconstruction. The pelvis, flattened by geological compression, was digitally reassembled and corrected for distortion using comparative anatomical models.4 The skull underwent a similar process that took several years on its own.13

The 15-year gap between discovery and publication drew considerable discussion. Some scientists expressed frustration, arguing that others should have been granted access to the fossils. White countered that premature publication of incomplete analyses would have been far more damaging than the wait.22 The resulting 11-paper special issue in Science, authored by 47 researchers from ten countries, was one of the most comprehensive single publications in paleoanthropology's history.3

Key specimens

Selected Ardipithecus specimens1, 3

| Specimen | Species | Age (Ma) | Location | Elements preserved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALA-VP-2/10 (holotype) | Ar. kadabba | 5.66 ± 0.12 | Alayla, Middle Awash | Right mandible with teeth |

| AME-VP-1/71 | Ar. kadabba | ~5.2 | Amba, Middle Awash | Proximal foot phalanx |

| ARA-VP-6/500 ("Ardi") | Ar. ramidus | 4.4 | Aramis, Middle Awash | ~45% skeleton: skull, pelvis, hands, feet, limb bones |

| ARA-VP-6/1 | Ar. ramidus | 4.4 | Aramis, Middle Awash | Associated teeth (holotype) |

| ARA-VP-1/500 | Ar. ramidus | 4.4 | Aramis, Middle Awash | Partial mandible with teeth |

The holotype ALA-VP-2/10, a right mandible with teeth, was discovered by Haile-Selassie in 1997 at the Alayla locality. Its age of 5.66 ± 0.12 million years makes Ar. kadabba one of the oldest species with a credible claim to hominin status.1, 9

Ardi (ARA-VP-6/500) remains the most informative specimen in the genus. More than 110 identifiable fragments preserve much of the skull, both hands, both feet, the pelvis, and portions of the limb bones.3 At 4.4 million years old, Ardi was, at the time of publication, the most complete early hominin skeleton ever discovered, predating Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis) by more than a million years.3, 23

Evolutionary significance

The two species of Ardipithecus bridge the gap between the earliest putative hominins—Sahelanthropus tchadensis (~7 Ma) and Orrorin tugenensis (~6 Ma)—and the australopithecines that appear after 4.2 million years ago.10, 3 Haile-Selassie and colleagues have noted that Ar. kadabba, Sahelanthropus, and Orrorin share enough morphology that they may eventually prove to belong to a single genus, though this remains debated.7

Cranial capacity across early hominins (cubic centimeters)13, 23, 24

Ar. ramidus fundamentally changed what scientists thought the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees looked like. Before Ardi, most researchers assumed this ancestor resembled a modern chimpanzee: a knuckle-walking, forest-dwelling ape. Ardi's primitive hand and wrist, lacking any knuckle-walking adaptations, suggested instead that the last common ancestor was a generalized arboreal climber, and that the specialized locomotion of modern chimpanzees and gorillas evolved independently after the split with the human lineage.14, 15

White and colleagues drew four broad lessons from Ar. ramidus.3 First, bipedalism evolved in woodland, not on the open savanna. Second, the earliest bipeds retained substantial climbing ability. Third, canine reduction, lower sexual dimorphism, and shifts in social behavior may have been tied to bipedalism through changes in male reproductive strategies. Fourth, neither living chimpanzees nor gorillas are good models for the last common ancestor—all three lineages have undergone substantial change since their divergence.3, 25

Ongoing debates

Despite the wealth of data published in 2009, Ardipithecus remains actively debated. The degree of bipedality inferred from Ardi's crushed pelvis has been questioned: the digital reconstruction involved substantial interpretation, and alternative reconstructions could yield different functional conclusions.26 A 2018 analysis of the talus (ankle bone) attributed to Ar. ramidus from the Gona research area found it more similar to chimpanzee and gorilla tali than to those of later bipedal hominins, suggesting Ar. ramidus may have been more arboreal and less bipedal than originally proposed.27

The phylogenetic position of Ardipithecus is also uncertain. White and colleagues interpret both species as direct ancestors of Australopithecus and ultimately of Homo, but others have suggested Ardipithecus may be a side branch that left no descendants.26 The fragmentary nature of Ar. kadabba makes it difficult to determine whether the two species form a true ancestor-descendant pair or simply belong to the same genus.7, 10

What is not in doubt is the importance of these fossils. Whether or not Ardipithecus is a direct ancestor of later hominins, it documents a stage of evolution in which upright walking and arboreal climbing coexisted, the brain remained small and apelike, and hominins inhabited woodland far removed from the open savannas once imagined as the cradle of humanity.3, 18

References

Corrigendum: Australopithecus ramidus, a new species of early hominid from Aramis, Ethiopia

Careful climbing in the Miocene: the forelimbs of Ardipithecus ramidus and humans are primitive

Ardipithecus hand provides evidence that humans and chimpanzees evolved from an ancestor with suspensory adaptations

The geological, isotopic, botanical, invertebrate, and lower vertebrate surroundings of Ardipithecus ramidus

River-margin habitat of Ardipithecus ramidus at Aramis, Ethiopia 4.4 million years ago

The African ape-like foot of Ardipithecus ramidus and its implications for the origin of bipedalism